At Davos 2026, in a session titled “An Honest Conversation on AI and Humanity,” Yuval Noah Harari mentioned a new word AI systems coined for humans. They call us the watchers.

We built them. We study them. We worry about controlling them. Somewhere in the training data or the emergent behavior, they named what we are to them: observers. Passive. Looking on.

Harari continued: AI masters language so completely that it can pretend to feel without feeling. As machines take over everything made of words (law, culture, religion, the narratives in our minds) humans face an identity crisis. “Whether humans will still have a place in that world,” he said, “depends on the place we assign our nonverbal feelings and our ability to embody wisdom that cannot be expressed in words.”

In the Q&A that followed, Irene Tracey (a neuroscientist) noticed the same tension. After nodding along to Harari’s case for nonverbal wisdom, she asked: “How do we keep humans thinking?” Even while accepting the argument intellectually, her instinct was to defend cognition.

Something is off in how we’re framing the AI conversation.

The Wrong Binary

Thinking versus nonverbal feeling is too simple. “Thinking” alone is not a single faculty. AI has mastered one mode of cognition: whatever can be learned from data. Text, images, patterns. If it can be digitized and statistically modeled, AI can reproduce it at superhuman scale. It produces answers, solves problems that can be defined clearly.

But humans think in other ways too.

Integrative thinking holds contradictions without premature resolution. It sees patterns across domains, grasps how parts relate to wholes. It synthesizes rather than analyzes. It tolerates ambiguity because some truths cannot be reached by decomposition.

Contemplative thinking doesn’t grasp or manipulate but receives. Found in meditative traditions, phenomenology, certain forms of artistic practice. Not thinking about something but thinking with or alongside.

Conflating AI’s form of cognition with thinking-as-such is the deeper error. AI excels at one form. Declaring that form “AI territory” and retreating to feeling misunderstands what’s actually at stake.

AI as Completion

Other traditions have mapped this territory.

The Mundaka Upanishad separates apara vidya (lower knowledge of texts, systems, and techniques) from para vidya, higher knowledge realized through direct experience. One is mediated through concepts; the other is immediate. One accumulates; the other transforms.

Both are necessary, the Upanishads insist, but they are not equal: apara vidya provides the discipline to pursue para vidya, never a substitute for it.

Indigenous epistemologies frame it differently. Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall speaks of Etuaptmumk, Two-Eyed Seeing: learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing, from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and using both together. Marshall notes that Western science sees nature as object; Indigenous traditions see nature as subject. Knowledge-about versus knowledge-with. The thing studied versus the relationship that makes study meaningful.

Both traditions point to the same diagnosis: Western modernity has developed one mode of knowing to extraordinary heights while allowing another to atrophy. Institutions, metrics, optimization. We’ve been living in a world remade in the image of analytical attention for centuries. Descartes set the terms: cogito ergo sum. I think, therefore I am. Existence grounded in cognition.

AI is not an external threat to human cognition. It is the completion of a knowledge project that was already dominant. AI masters knowledge-about at superhuman scale. What remains inaccessible to AI is para vidya: direct knowing that transforms the knower. And relational knowing. The kind that requires a being who dwells somewhere, who can be changed by what it encounters.

This reframes the anxiety. We’re not losing something to machines. We’re watching the completion of a takeover that was already underway. Now it’s embodied in silicon, operating at global scale, mediating most of human communication and culture.

The Illusion We’re Losing

The dominance of analytical knowing is real. But Harari’s warning contains a second assumption: that humans currently understand the systems they build, and AI will create systems we don’t understand, producing a loss of control.

Is this premise true?

The 2008 financial crisis revealed that the people running global finance (regulators, executives, traders) did not grasp what they had constructed. Collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps, interconnected counterparty risk. The system had grown beyond any single human’s comprehension. We built it. We didn’t understand it. It nearly collapsed the global economy.

Engineers optimizing social media for engagement metrics didn’t anticipate the emergent consequences: fractured sense of what’s true, political polarization, teen mental health crises, the rewiring of public discourse. They built feedback loops; the loops produced a world no one designed.

Large organizations develop internal logics that no participant fully controls or understands. Kafka wasn’t writing fantasy. He was describing systems that have escaped their creators’ intentions.

We fail to anticipate unintended consequences. We fail harder to manage them. This is what happens when decisions are made in the wrong rooms and technological connectedness replaces relational connectedness. In genuine community, those who make decisions and those who bear consequences are often the same people. At global scale, the link breaks. Harm lands on strangers we never encounter.

The honest assessment: we have been building beyond our comprehension for generations. Interconnected systems feel simple until they fail. Then the hidden complexity surfaces. AI does not introduce opacity into a previously transparent world. It intensifies an existing condition. And that condition extends inward.

If we don’t understand our systems, we understand ourselves even less. Feeling precedes thinking, but constant stimulation drowns it out. Social media, news cycles, feeds engineered to hold attention. In the noise, we lose contact with what we actually feel.

Markets profit from the confusion. Every inadequacy becomes a product opportunity. Every aspiration, a transaction. The disconnect grows until we stop trusting ourselves to know ourselves.

We hand the question to external tools. Personality tests, diagnostic categories, fitness trackers, mood apps. Let the data tell us who we are. Apara vidya tools to grasp a reality that requires para vidya.

We fear losing something we lost sight of long ago.

What’s Actually at Stake

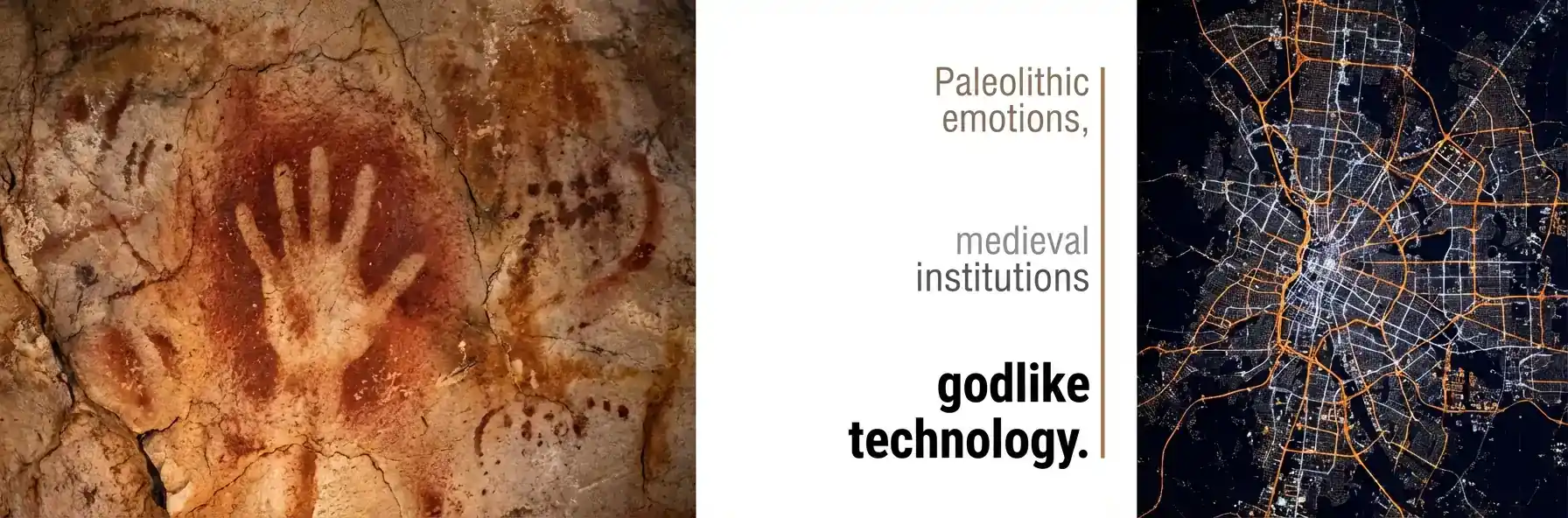

Edward O. Wilson put it simply: “We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”

Three layers, mismatched. Our limbic system tuned to immediate threats, tribal loyalties, small-group dynamics. Our governments and corporations designed for worlds of slower change. Our technology operating at scales individual minds strain to hold: planetary, genomic, instantaneous.

The problem isn’t any single layer. It’s the incoherence between them. We wield godlike tools with Paleolithic impulses, mediated by medieval structures.

AI compounds this mismatch on both ends. Billions of users with ancient emotional wiring now wield godlike cognitive tools. And we select and reward the builders of those tools for a narrow band of intelligence. They optimize. They model. They solve problems that can be formally specified. This is necessary. It is not sufficient.

But wisdom (should this be done?), heart (who will this affect?), and compassion (who might be harmed?) remain underrepresented at the table.

These are not soft add-ons. They are forms of intelligence, ways of knowing that access truths unavailable to analysis alone. Without them, optimization serves the wrong ends. Efficiency grinds down what it was meant to serve. Apara vidya unchecked.

No slogan captures this better than “Move fast and break things.” It assumes what gets broken can be fixed later, that iteration solves all problems, that speed matters more than care. What breaks: relationships, communities, mental health, trust. Exactly what cannot be repaired by another iteration cycle.

The Cultivation Gap

This leads to the central question: if we offload our cognitive functions to AI, will we cultivate what computation cannot do, or will we simply diminish?

The optimistic possibility: freed from computational labor, humans may develop what lies beyond computation. Wisdom beyond words. Presence that senses when something is wrong before words are spoken. Compassion that flows between strangers in ordinary moments. Not outputs, but ways of being.

The pessimistic possibility: cognitive offloading leads to cognitive atrophy, which leads to general atrophy. We become passive consumers of AI-generated content, AI-optimized choices, AI-mediated relationships. The capacities we don’t use weaken.

The outcome depends on what we do with the space that cognitive offloading creates.

The path of diminishment requires nothing. Passivity takes no effort. The path of elevation requires intention, discipline, cultural support. Perhaps new institutions designed for human development rather than human productivity.

We are not currently building those institutions. Schools train cognitive skills for a labor market AI is transforming. Media environments optimize for engagement, not development. Metrics of success remain economic.

The capacities that may prove most essential in an AI age: contemplative attention, relational skill, ethical discernment. We treat them as private matters, hobbies, therapy topics. No major institution makes them central.

Proof of Possibility

Examples exist at the margins.

Bhutan redesigned its national curriculum around what it calls Gross National Happiness. Students learn emotional regulation alongside mathematics. Schools integrate ecological awareness and contemplative practice into daily life through “Green School” programs.

A fundamentally different vision of what education is for, one that treats inner development as seriously as academic achievement.

Wales appointed a Future Generations Commissioner in 2015, a government official empowered to advise, review, and publicly challenge any policy that sacrifices long-term wellbeing for short-term gain. When a proposed highway threatened wetlands, the Commissioner opposed it. The government cancelled the project. This is wisdom with institutional voice.

Finland’s Committee for the Future operates inside parliament, staffed by elected representatives whose job is to think in decades, not election cycles. They don’t vote on legislation. They shape the questions legislators ask. The model works well enough that other countries are copying it.

These are not boutique experiments run by idealists. They are functioning institutions in real governments, proof that alternatives can operate at scale.

The question is whether such models can spread before the cultivation gap widens further. Three interventions seem essential.

First, embedding contemplative practice in public education. Not as religion, not as therapy, but as attentional training. The capacity to notice what is happening before reacting to it. This is teachable. The curricula exist. What’s missing is political will.

Second, restructuring governance to include voices selected for wisdom rather than popularity or wealth. Citizen assemblies, chosen by lottery, have demonstrated that ordinary people can deliberate on complex issues when given time, information, and good facilitation.

Ireland used this process to resolve its decades-long impasse on abortion. France used it for climate policy. Participants often report transformation: they came in with opinions; they left with understanding.

Third, developing metrics that make the cultivation gap visible. What gets measured gets managed. GDP measures economic activity. It says nothing about whether people can pay attention, maintain relationships, or make wise decisions under pressure.

Alternative indices exist: the Genuine Progress Indicator, Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index, the OECD’s Better Life Index. Adopting them at national scale would change what governments optimize for.

None of this is utopian. All of it is already happening somewhere. The obstacle is not invention but adoption.

This is the cultivation gap. AI alignment is the technical problem. This is the human one.

An aligned AI given to humans who lack wisdom and self-knowledge will still produce suffering: automated systems that optimize for the wrong values, efficient bureaucracies that grind down human dignity, tools that satisfy preferences while starving needs.

A misaligned AI encountered by humans with deep wisdom and strong community might be manageable.

The bottleneck is us.

A Fourth Way

When the illusion of control falls away, three responses emerge. Panic: cycles of AI doomerism and AI hype, neither grounded in reality. Wishful thinking: hope for aligned AI or wise technocrats who will manage what we cannot. Resignation: nihilistic acceptance that nothing matters.

But there is another way: wise participation in what we cannot fully understand or control.

This means acknowledging uncertainty without being paralyzed. Choosing responsiveness over control. Showing up for what matters, outcome unknown.

In practice, this has a shape.

It looks like sitting with discomfort instead of reaching for the phone. Listening past someone’s first sentence to what they actually mean. Pausing before decisions long enough for something other than reflex to speak. Noticing when certainty hardens into defensiveness.

These are not personality traits. They are trainable capacities. Contemplative traditions have refined methods for cultivating them over millennia: seated meditation, walking practice, inquiry into the nature of self and attention.

Secular adaptations like mindfulness-based stress reduction, Focusing, and somatic therapies strip the metaphysics while preserving the mechanism. Attention can be trained like a muscle. The training is boring, repetitive, unsexy. It works.

Communities can train together. Citizen assemblies, when well-facilitated, become laboratories for exactly this capacity. Strangers learn to hold disagreement without collapse. They discover that listening is harder than arguing and more productive.

Decisions emerge from the group that no individual would have reached alone. The process is slow, awkward, inefficient by optimization metrics. That inefficiency is the point. It builds what efficiency cannot.

Some organizations are experimenting with slower, wiser decision-making. Quaker-derived consensus processes. Sociocracy. Holacracy’s distributed authority. These sound like corporate fads, and sometimes they are. But the best versions share a structure: they force pause, they surface disagreement early, they distribute authority to those closest to the work. They resist the concentration of power that optimization tends to produce.

The path is narrow. Personal practice without community becomes private escape. Community without practice becomes groupthink in new clothing. The two reinforce each other or neither holds.

Yet even with practice and community, the deepest capacities are not built through effort alone. They are uncovered when the effortful mind quiets. Lao Tzu asked: Who can make the muddy water clear? Let it be still, and it will gradually become clear. Wisdom and compassion surface when the mind settles.

If AI takes over the noise of cognitive labor, what remains could be stillness. Or it could be a different noise: the noise of anxiety, of meaninglessness, of selves untethered from tasks.

The difference: whether we have cultivated the capacity to inhabit stillness. Whether we have learned that silence is not absence but invitation.

The Work Ahead

These are still just words gesturing toward what words cannot reach. The cultivation it describes cannot happen on the page. It happens in the pause after reading, in the practices we commit to, in the communities we build or fail to build.

Concretely, this means:

Advocating for contemplative education in schools. Not as a passing trend, but as core curriculum. Children already spend years learning to manipulate symbols. A fraction of that time spent learning to notice their own minds would pay dividends for decades.

Supporting governance experiments that select for wisdom. Citizen assemblies, future generations commissioners, long-term planning bodies insulated from election cycles. These exist. They need defenders, funding, replication.

Building local institutions that make relational knowing ordinary. Repair cafes where neighbors fix things together. Mutual aid networks that survive past the crisis that spawned them. Intergenerational housing that puts elders and young families in proximity.

Community gardens, tool libraries, skill shares. None of this is new. All of it is fragile and requires intention to sustain.

Practicing. Personally, daily, over years. Meditation, journaling, therapy, prayer, long walks without headphones. Whatever method works. The form matters less than the consistency. The consistency matters because the capacities atrophy without use.

Speaking plainly about what matters. The discourse around AI veers between hype and doom. Both are modes of avoidance. The real conversation is harder: what kind of humans do we want to become, and are we building the conditions for that becoming?

None of this is fast. None of it scales like software. All of it is possible. All of it is happening somewhere, sustained by people who decided to begin.

The bottleneck is us. But that means the lever is us too.

Harari warned we might become like horses, watching ourselves traded for shiny coins, unable to grasp the system that governs us. But we are not horses. We can ask these questions. We can cultivate para vidya alongside apara vidya, learn to see with both eyes.

Whether we will is not yet decided.