There’s a recurring pattern in AI conversations: decision-makers gathered in rooms discussing surface-level concerns while fundamental transformations occur unnoticed. A leader asks, “What should our AI strategy be?” A reasonable but ultimately misguided question.

The Factory Case Study

Consider early 1900s American factories powered by line shaft systems. Massive steam engines driving horizontal shafts along ceilings connected to machines via leather belts. This architecture constrained everything: machine placement, building design, lighting, worker safety.

When electricity became available, factory owners initially simply replaced the steam engine while maintaining the entire infrastructure. The breakthrough came through “unit drive”: attaching small electric motors directly to individual machines. This eliminated the need for shafts, allowing factories to reorganize around actual workflow rather than power distribution constraints.

Henry Ford’s River Rouge plant exemplified this transformation, organizing 1.6 million square meters of single-story production around material flow efficiency.

Economist Paul David documented a “productivity paradox”: transformative technologies often disappoint for decades before potential is realized.

Electricity took approximately 40 years from Edison’s 1882 Pearl Street Station to productivity surges in the 1920s, when total factor productivity jumped over 5% annually, with electricity accounting for roughly half those gains.

The AI Parallel

The same pattern repeats with artificial intelligence, but with a critical difference: decision-making authority resides in the wrong organizational locations. Leadership asks strategic questions. IT addresses technical implementation. But the people who understand daily friction, workarounds, and operational constraints, those positioned to identify genuine AI opportunities, aren’t in either room.

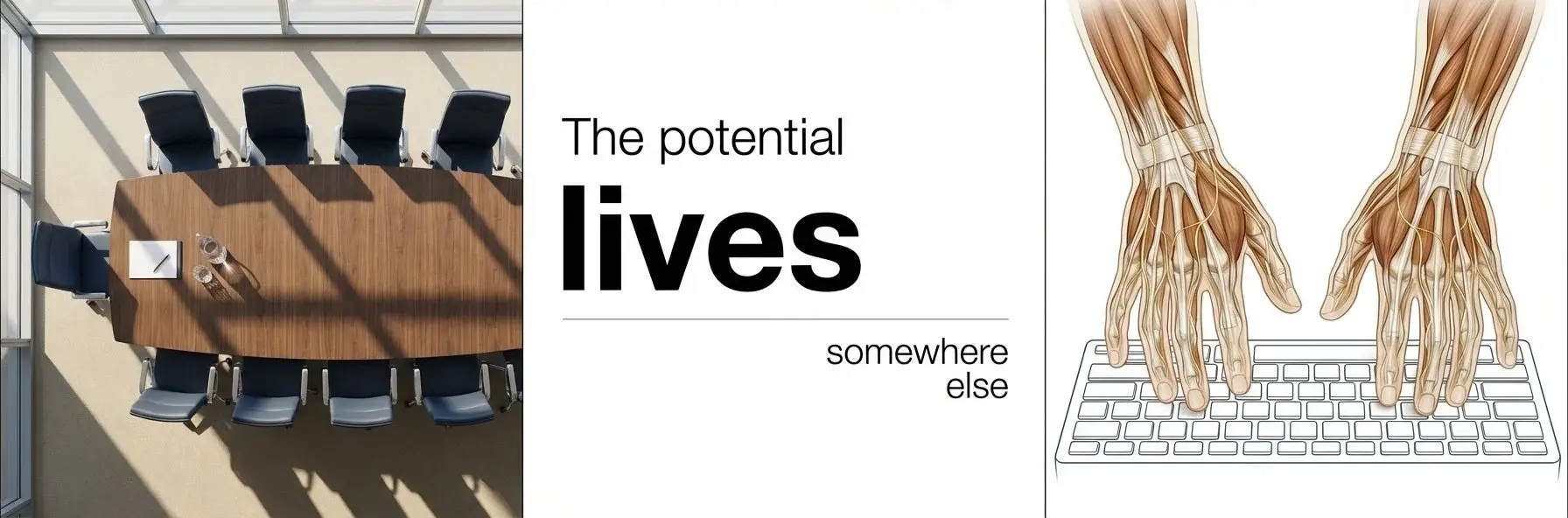

“The decisions happen where expertise seems to live. The potential lives somewhere else.”

Workers navigating invisible inefficiencies (excessive clicks, undocumented workarounds, unnecessary meetings) possess detailed knowledge of where friction exists. They now have tools to address these problems, but lack authority or visibility to do so.

The Delegation Trap

When leadership delegates AI to IT, rational logic breaks down. IT frames problems through security, integration, and platform selection. Infrastructure concerns rather than operational transformation. Success becomes “it works” rather than “we operate differently.”

Meanwhile, the combination of subject matter expertise, AI capability, and operational knowledge lives in contexts IT rarely touches.

A Different Structure

What if AI ownership transferred to Business Development and Communications rather than IT? Business Development thinks in opportunity and possibility across silos. Communications professionals excel at articulation and precision, skills fundamental to AI interaction quality. These functions sit at the bridge between operations and strategy, positioned to surface invisible potential while influencing direction.

This represents a power redistribution: IT shifts to infrastructure role (like electricians in newly wired factories), not strategic ownership. Leadership’s responsibility becomes enabling distributed problem-solving rather than directing AI initiatives.

People must move from asking “What should our AI strategy be?” to “How do we create conditions for the invisible to surface?”

The Urgency Factor

Unlike the 40-year timeline for electrification, AI development accelerates rapidly. Organizations redesigning workflows around AI capabilities will compound competitive advantages annually against competitors still optimizing legacy structures.

Transformation will emerge not from better technology but from better imagination.

The essential question shifts from technical strategy to philosophical orientation: “If we could design this from scratch, knowing what AI makes possible, what would we build?”

The Core Challenge

For most organizations (bakeries, agencies, logistics firms) AI isn’t their product. Yet treating it as such creates misaligned questions. The real opportunity lies in identifying normalized constraints so familiar they’ve become invisible, then asking whether those constraints remain necessary.

Transformation requires courage to accept ongoing redesign rather than treating AI as a one-time implementation project. Organizations must recognize that the rooms where AI decisions happen today are not the rooms where AI value will be created.