Something I didn’t anticipate when I started this work: the most revealing moments rarely happen during the session itself.

I was onboarding a CEO and board member, walking her through how to work with AI in her own context. She was sharp, engaged, picked things up quickly. We covered what we needed to cover. And then, as we were wrapping up, she told me she felt guilty.

Not about anything we’d discussed. About using AI at all. Decades of professional ethics had taught her that relying on this kind of support felt like cheating. The work wasn’t fully hers anymore, or so she feared. She’d been carrying this quietly, and something in the session had made it safe enough to say out loud.

I hear this more often than you’d expect. Not always the word “guilty,” but the feeling beneath it: a suspicion that accepting help from AI diminishes the value of what you produce. That it makes you less, somehow. That real professionals shouldn’t need it.

What Counts as Yours

What dissolved the guilt was not a technique or a reassurance. It was a recognition.

She already did the thing she felt guilty about. Every draft she wrote, she shared with trusted colleagues before finalizing. She gathered perspectives, invited challenge, refined her thinking against other minds. This is what good thinkers do. It is also exactly what she was doing with AI.

The source had changed. The practice hadn’t. Once she saw that, the guilt lost its footing. It wasn’t about the technology. It was about a story she’d been telling herself about what counts as her own work.

Montaigne, the sixteenth-century essayist who invented the personal essay as a form, built his entire method on other people’s ideas. He quoted, borrowed, argued with, and rearranged what he’d read, and through that process discovered what he actually thought. “I quote others,” he wrote, “only in order the better to express myself.” He never considered this a failure of originality. He considered it the work itself.

The anxiety about authorship, about what is truly “mine,” is older than any technology. AI didn’t create it. AI made it harder to avoid.

The Polarity Nobody Talks About

That conversation stayed with me because it points to something adoption statistics never capture. AI, unlike any workplace tool before it, surfaces questions about identity and self-worth.

Knowledge workers who’ve built careers around how they think face a specific version of this. Strategy, analysis, synthesis, judgment: these capacities defined their value for decades. Now a tool that approximates parts of that work is available to everyone, improving at a pace no individual can match.

Watch the timelines. The gap between what AI could do last quarter and what it can do now is often larger than a person’s own growth over the same period. People notice this, even when they don’t say it.

The result is a polarity that most conversations about AI fail to hold. You can build things now that were unimaginable a year ago. People are creating their own tools, prototyping ideas, operating at a scale that would have required entire teams. And at the same time, the pressure to keep pace with the technology’s acceleration can make your own development feel glacially slow by comparison.

Both of these are true simultaneously. The empowerment is real. So is the unease. Most people only talk about one.

Staying with the Friction

I’ve written before about what AI reveals about how we think: the way a failed prompt exposes the gap between what we believe we know and what we can actually articulate. That gap is one of AI’s most underappreciated gifts. But there is a step beyond it most people don’t take.

When the output misses the mark, the instinct is to blame the tool. The model isn’t good enough. Try a different prompt. These responses treat AI like a vending machine that dispensed the wrong item.

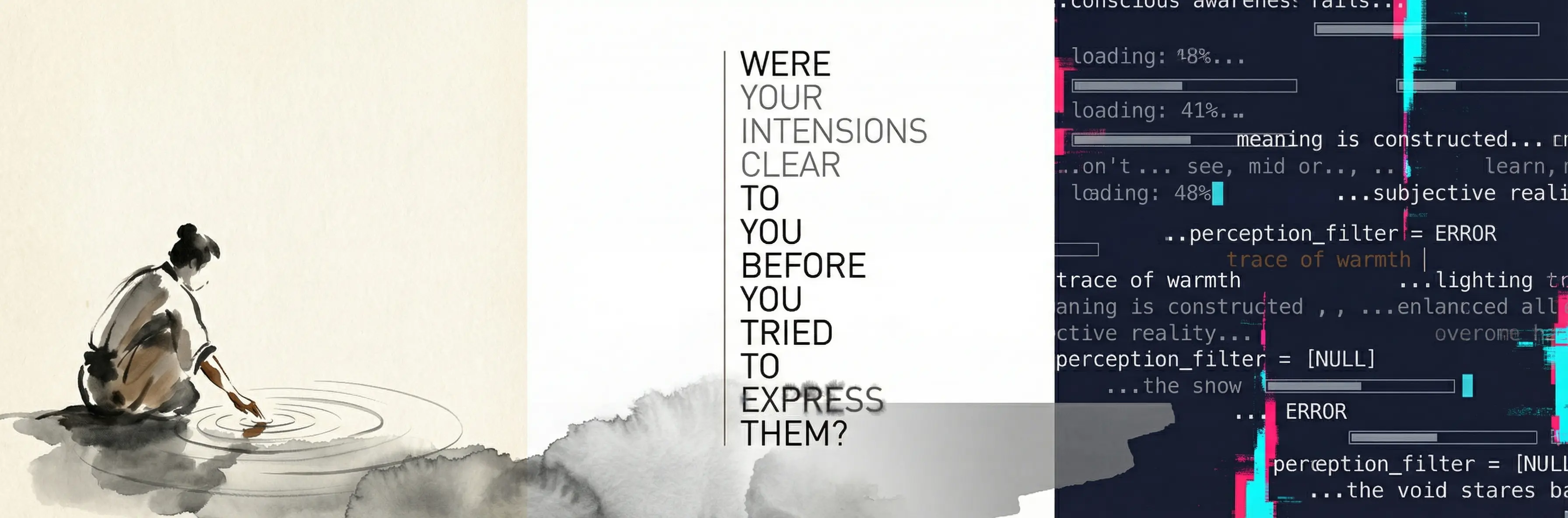

The alternative is to stay with the friction. To ask what it reveals. Were your intentions clear to you before you tried to express them? Did you know what you wanted, or were you hoping the machine would figure it out?

No tool before AI has confronted us this directly with the quality of our own thinking. A search engine retrieves. A spreadsheet computes. Neither asks whether your question was well-formed. AI does, because it attempts to execute on your ideas and shows you, without diplomacy, whether those ideas were actually coherent.

In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates warned that writing was a dangerous technology. A written text cannot answer questions. It cannot clarify itself. It repeats the same words regardless of who reads them, offering what Socrates called the appearance of wisdom without the living exchange that produces understanding. For twenty-four centuries, every information technology confirmed his concern. Books, newspapers, search results: all one-directional. All static. None capable of dialogue.

AI breaks that pattern. For the first time, a cognitive tool talks back. It responds to what you bring. It produces different outputs depending on how clearly you think. When you dismiss the friction, you get what Socrates feared: the appearance of productivity without understanding. When you stay with it, you get something closer to what he valued: a dialogue that forces you to clarify, reconsider, and think again. The partner is different. The mechanism is the same.

The Absence of Judgment

There’s a dimension of working with AI that I don’t see discussed enough: the privacy.

It is one to one. No audience. No reputation at stake. Unlike a team meeting or a client presentation, there is no social cost to getting it wrong. No one is watching.

Donald Winnicott, the psychoanalyst, described what he called “potential space”: a psychological zone where play, creativity, and experimentation become possible because judgment is absent. A child plays freely when no one is evaluating the play. An adult stops playing when every action carries consequence.

AI creates something like this, almost by accident. A space where you can try an idea without committing to it publicly. Where you can test the edges of your capability without risking your standing. Where “what if” carries none of the weight it normally does in professional life.

I watch this happen with the executives and senior professionals I work with. Once the guilt dissolves and the friction becomes familiar, something opens. Ideas that stayed abstract for months begin to take shape. Creativity emerges. Not the kind the model generates, but the kind that surfaces when a person starts experimenting without fear of failure.

What follows is counterintuitive. The process builds self-confidence. Not confidence in the AI. Confidence in themselves. When you use AI to bring an idea to life that you’d assumed was beyond your reach, something shifts in how you see the technology. It stops feeling like a threat. It starts feeling like an amplifier for capacities that were always there, waiting for a low-stakes space to emerge.

The Variable

None of this is about better prompts or smarter workflows. Those have their place, but they’re not the main event.

The main event is what happens when you stop treating AI as a tool to be mastered and start noticing what it surfaces about you. Your clarity. Your assumptions. The places where your thinking was less formed than you believed. In a world where everyone has access to the same AI, the variable was never the technology. The question isn’t whether AI risks making us lazy thinkers. It’s whether we choose to let it.

The people who get lasting value from AI are not the ones with the best techniques. They are the ones willing to do slower, less visible work: understanding what they uniquely bring. Their judgment, their perspective, their capacity to sense when the AI is wrong and why. These capacities don’t develop by using AI more. They develop by paying attention to what happens when you do.

The CEO stopped carrying her guilt when she recognized something she’d known all along. Good thinkers have always gathered feedback. They’ve always tested their ideas against other minds. The source changed. The practice didn’t.

But I also told her what I tell everyone who reaches this point: hold on to the human connections you already rely on. The people who know your work, who know your blind spots, who can read what you mean beneath what you say. AI can pressure-test a first draft. It cannot replace a colleague who has watched you grow over years and knows exactly which question will make you think again.

The technology is the same for everyone. What you bring to it isn’t. And what you choose to protect alongside it may matter just as much as how you use it.